THE IMPORTANCE OF STRUCTURED TRAINING

True program design is an art. There are so many details and factors to consider when crafting a periodized training program.

When crafting programs for clients at WhittleStrength, we tend to focus on a couple key components - training frequency, establishing reps, progressive overload, implementing a proper warm up.

How often should you train? Training frequency depends on a few factors. For one, a beginner shouldn’t go from zero exercise to training 5x a week. A beginner should aim for ~2x a week to start, with the intent to slowly increase frequency over time. On the other hand, an advanced lifter can get away with lifting 5 days a week as the body is adapted to this type of stress. For an athlete, a limiting factor could be the season they are in. For example, an in-season high school athlete will only weight train ~1-3x a week depending on practice/game schedules and the duration of the session itself (i.e. if only 30 min sessions you could train 3x a week, where a 1 hour session might only take place 2x a week). An off-season athlete who has little to no sport practices/games might train ~4-5x a week.

Lastly, one factor that often gets overlooked is what the client is dealing with in their personal life. For example, a nurse who works over 8 hour shifts 5x a week, is always on their feet, doesn’t get enough sleep, nor eats enough in a day, should not be trying to lift 5x a week and run 4x a week. They will put their body into a chronic state of overtraining and are at risk for things like injury, lowered immune system, and chronic elevated levels of cortisol. On the other hand, a competitive athlete who focuses primarily on their sport can get away with this frequency of training if they are able to get enough recovery/sleep and are eating a nutrient rich diet.

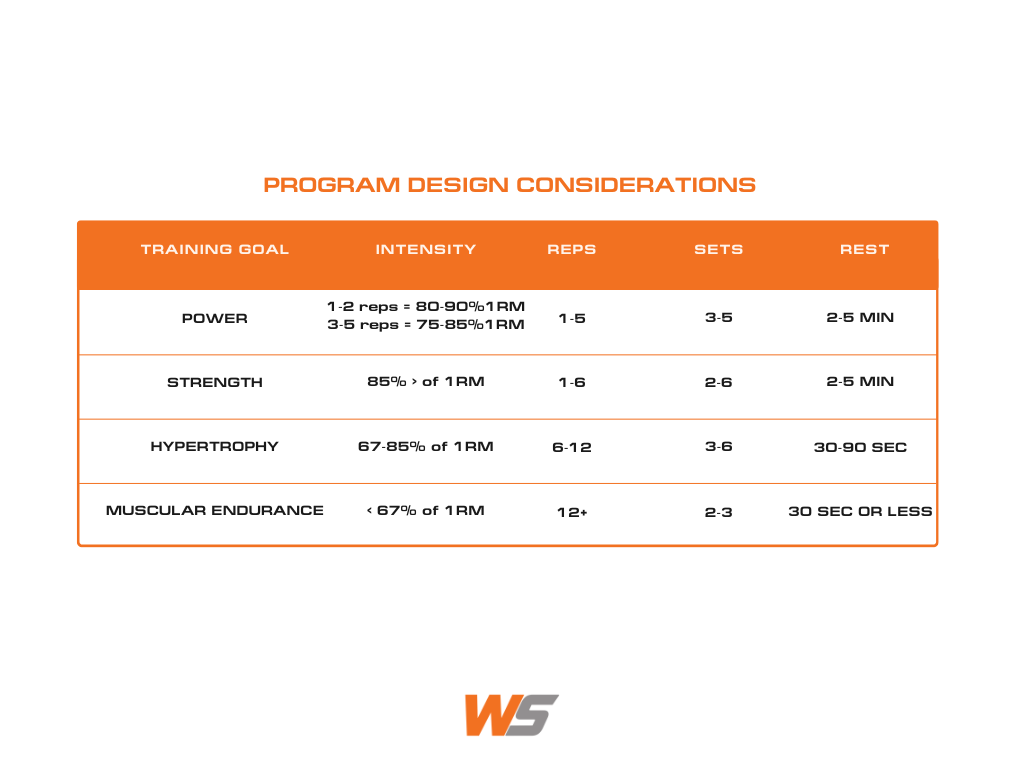

How many reps should I to do? Your training goal directly dictates your intensity, reps, sets, and rest periods. With weight training you can vary your goal overtime. For example, starting out your goal might just be to learn proper movement patterns and gain overall strength. Eventually, your goal might be to put on some serious muscle mass and maybe a year later you may change your mind and decide you want to improve your muscle endurance and start training for a half marathon.

As your training goals change, it’s important to understand that your intensity, reps, sets, and rest periods need to change to align with that goal in order to achieve these certain adaptations.

The table below from the NSCA illustrates some of the common program design considerations based on the training goal.

Sets and reps are great, but you need to progress in the gym too. Progressive overload is another key consideration with crafting a training plan that may often be overlooked. Progressive overload can be defined as, “a principle of resistance training exercise program design that typically relies on increasing load to increase neuromuscular demand to facilitate further adaptations” (Plotkin, 20220). Simply put, if you constantly lift the same weight week after week your body will plateau. Progressive overload doesn’t always have to be increasing weight, you can also cause further adaptations on the body by increasing reps, number of sets, or even by making the tempo longer. However you chose to implement progressive overload, doing so presents the body with new stimuli that acts as a stressor to the neuromuscular system. In turn, the body will adapt to the new stimuli causing new muscle proteins to be created, increases in muscle fiber size, and strength adaptations to occur. This stimuli will also lead to adaptations of the ligaments, tendons, joints, and bone formation.

Should I warm up? A structured warm-up before getting into the heavy lifting is important for human physiology for many reasons. One way to approach a warm-up is to follow the principle of RAMP. Ramp stands for raise, activate, mobilize, and potentiate.

Raise - increase muscle and core temperature, blood flow throughout the body, muscle elasticity, and neural activation/drive. Increasing body temperature and blood flow before going into a heavy lift is important because it lowers the risk for injury. For example, biking for 3 minutes as the first part of the session can help to increase heart rate, blood flow, and body temperature.

Activate - It is important to engage the working muscles in order to prepare them for the upcoming session/exercises. For example, performing a banded glute bridge to help engage the gluteus medius, a muscle that is important when back squatting.

Mobilize - Here you should focus on specific movement patterns that you will be performing during the workout. For example, performing body weight squats and lunges focusing on ankle dorsiflexion in preparation for a back squat.

Potentiate - gradually start to increase the stress/intensity on the body. For example, warming up with the bar then performing a few warm-up sets before getting into your working sets of back squat.

Plotkin, D., Coleman, M., Van Every, D., Maldonado, J., Oberlin, D., Israetel, M., Feather, J., Alto, A., Vigotsky, A.D., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2022). Progressive overload without progressing load? The effects of load or repetition progression on muscular adaptations. Peer J, 10.

Share this post: